Can We Have a Word? Talking Gendered Linguistics with Elle Graham-Dixon.

Saata is an Art Director who has worked in the advertising, marketing, non-profit and ad tech industries. As a three-time winner of Graphic Design USA’s American Graphic Design Awards, her work is both diverse and well-recognized. Saata was born and raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, but now calls Los Angeles home. She is a proud first-generation American whose family is from Sierra Leone, West Africa. This drives her passion for diversity, inclusion and mentoring up-and-coming talent. When she’s not kickboxing or watching the latest Broadway musical, you can find her painting, dancing or discussing anything pop culture-related.

Since diversity is such a trendy topic these days, it can be hard to know how to talk about it in an informed and empathetic way. Elle Graham-Dixon’s keynote explored how words themselves add to the challenge of talking about diversity. The biases inherent in language often leads us to stereotype and exclude. Graham-Dixon took the audience on a journey of thorough breakdowns of the gender-based constructs of language and how these foundations have developed and shaped the way we see the world. All throughout, she provided the audience with a blueprint of how we can all speak up and better choose our words because words have power.

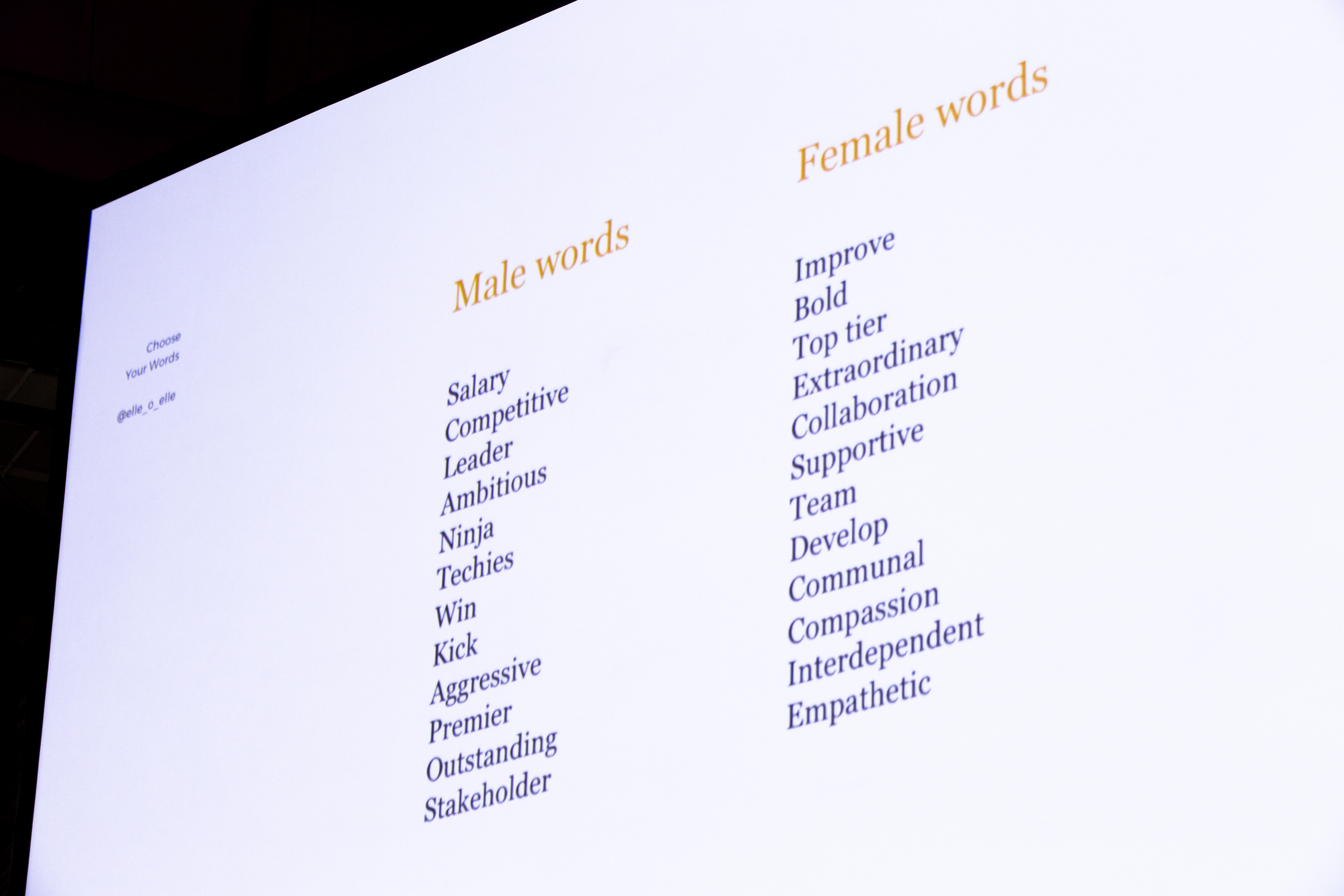

Gendered linguistics are interlaced into our everyday lives in both subtle and obvious ways. Graham-Dixon discussed how certain words skew masculine and others skew feminine. She brought up an article from The Financial Times that discussed gender-decoding technology for job descriptions. This technology screens the words in the job description to see if it is leaning more male or female. As Graham-Dixon said, “The data doesn’t lie – the words on the right do code more to the imagery that women are associating themselves with.”

Graham-Dixon then proposed a contemplative question to the audience: “Should we really justify rewriting our job descriptions to include those female words? And should we be calling them male words and female words in the first place? Surely, that’s the problem.” There was not an answer given, but it’s interesting to think about how the results might differ if words that code more male, like: salary, competitive, leader and outstanding, and were replaced with words that currently code more female, like: bold, supportive and empathetic, in job descriptions and other written bodies of work.

As Graham-Dixon explained, “Language reinforces the status quo…We can talk about change, but if the tool we have to talk about change is broken, is based on a gender binary, is based on a sex-based system, then the more we talk about change, the more we risk perpetuating the status quo if we don’t look to break the system first.”

Graham-Dixon went on to dig a little deeper into the DNA of language and explore what the foundation of language currently looks like. Some of the data points she introduced into the discussion were:

- 75% of the world’s languages uses a sex-based system

- Every language spoken today makes some type of gender distinction

- The languages we use include an extreme amount of pronouns. In fact, 90% of the pronouns used across Reuters news are male

One of the biggest points drawn out of this data is that pronouns are very powerful. She explained, “When you’re reading a piece of text, pronouns have a power that goes beyond the structures we’ve grown up with and the way that we’re currently coding women and coding men… As a child, you understand the world through putting words and labels on it. If you don’t, your sense of that meaning is lost.” Essentially, the basis of gender linguistic theory is that words form thoughts and thoughts form words.

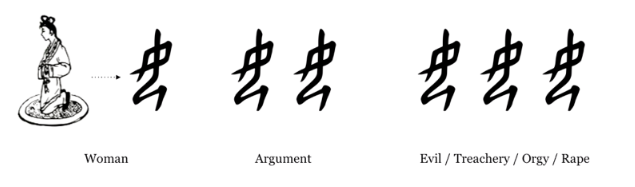

To further illustrate how language can inform and sometimes dictate our own relationship with gender-based biases and notions, Graham-Dixon presented an image of the Chinese character for the word “woman.” Two of these characters together form the word “argument.” And three of these characters together form the words “evil/treachery/orgy/rape.” However, the Chinese character for “man” and the character for “woman” together form the word “good.” This is a stunning example of how societal and institutional norms have allowed for the value of a woman to be vetted through the consignment of a man.

Going into how language influences literature, Graham examined the rampant culture of male editorship and authorship. For instance, the Oxford English dictionary, which is an English language institution in and of itself, has exclusively had male editors since it was founded in 1879 – seven total, to be exact. And in this digital age, “the Internet promised an equality of authorship,” as Graham-Dixon put it, but that hasn’t really been the case. Take Wikipedia, for example. Ninety percent of the platform’s content is still edited by men. What this means is that Wikipedia, which has become the unofficial digital encyclopedia, has its content’s voice being controlled by men, who make up only fifty percent of the population. “Women are opting out and language is forcing them to do that. The structure remains broken,” Graham-Dixon added.

She continues to explain that “this is exactly what The Patriarchy means. It is the structure and the system that perpetuates and maintains patriarchal values. The sexist society has created a sexed language; but in turn, the sexed language reinforces the sexist society.” It’s a trap we must work together to break out of.

So what can we do about this? One thing to understand is that we can all create change because we all have language. We all have unique voices, but we all can actively choose to use language that disrupts the patriarchy and does not perpetuate the status quo. Graham-Dixon said that unconscious bias training is a great start because it allows us to recognize our own biases, which allows us to be "agents of change” in our own communities. We all have biases and assumptions, but they cannot be changed if they are not first recognized.

At the end of her keynote, Graham-Dixon highlighted three distinct ways we can all create change:

- Rebuild language. In order to do this, we can start with how we identify ourselves, particularly on the gender spectrum. Graham asked the audience to raise their hands if they identified as 100% male. Then to keep their hands up if they identified as being 100% masculine at all times. The hands tended to go down during this second request.

The point is that gender and gender identity is not rigid. The foundation of our existence has been forcing us to choose only between male and female, but the fact is that the gender landscape is fluid. The more we can expand our understanding of and conversations around gender identity from “male/female”, “masculine/feminine” and “trans/androgynous” to include more words like “cis”, “agender”, “bigender” and “gender fluid”, the more we can create a more all-encompassing representation of what gender identity truly can be.

“(We can) use language to describe, rather than label,” noted Graham-Dixon. Language can be used to explore and provide empathy for those who have been historically been “other-ed” by words.

- Use words differently. We can rewrite the code to words by rewriting the associations to them. The Face + Body campaign from ASOS is redefining gender associations by showing that makeup can be for both men and women because we all have a face and we all have a body, and it’s for everyone’s viewing pleasure, not just for men and not just for women. Graham-Dixon said that it’s the responsibility of advertisers and of people responsible for brands to create these gender-inclusive spaces.

- Create new words. The algorithm of the Oxford English Dictionary still heavily uses data from the internet and is based on the usage of words. Graham-Dixon said we have the power to change what words become common and ingrained into the fabric of our language by what we write online. We essentially can change language through a tweet (or a blog post). Some of the most interesting words added to the Oxford English Dictionary this year due to huge upticks in usage across the Internet include “mansplain”, “lactivist” and “Mx”.

At the end of her keynote, Graham-Dixon left the audience with actionable insights to help us navigate conversations around diversity and inclusivity from an informed perspective. In the sometimes divisive world we live in, we can help by understanding the origins of the words that greatly inform our individual and collective experiences. Society is changing, and thus, so is language. How will you help shape this change?

Watch her talk below: